ChatGPT: Looming Threat or Useful Tool?

It’s an emerging technology that has the academic world – teachers, scholars and even students – in a frenzy. OpenAI’s ChatGPT is an online chatbot capable of outputting information with a level of detail and coherence previously unknown in the technological world, and people have quickly taken notice.

Following the publicization of the technology, questions quickly emerged over whether students could use it to cheat at school – and it seems they can. Many individuals have tried putting essay prompts into ChatGPT, and the results that it produced were, in more than a few cases, passable. This has led to numerous concerns over the implications of ChatGPT in schools – and its implications for writing as a medium.

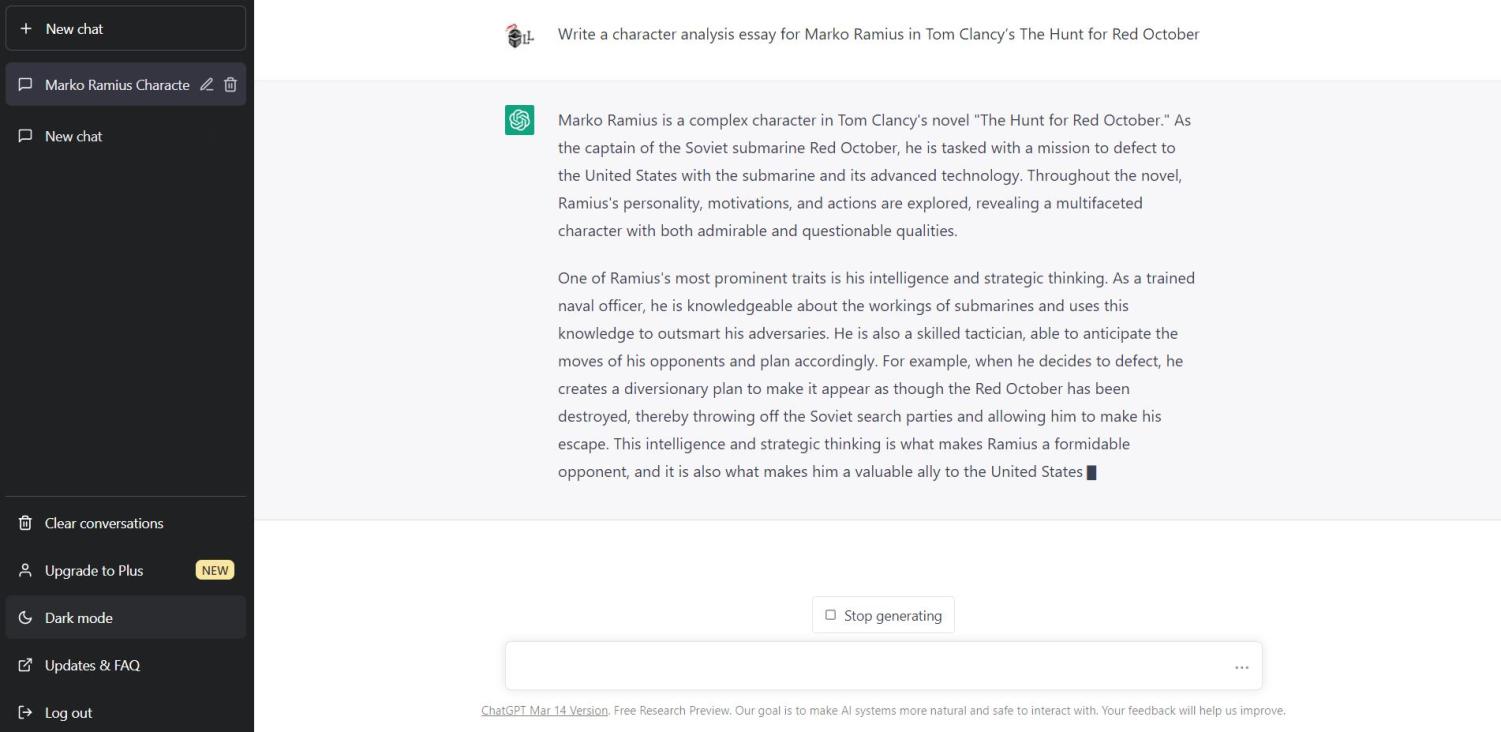

Consider trying it out. Pick a book you like, and ask ChatGPT to write an essay. For example: “Write a character analysis essay for Marko Ramius in Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October.” Don’t feel limited – pick any subject and essay type you want, and see for yourself what it can produce.

What is ChatGPT: A Closer Look

ChatGPT is, in simplest terms, a text generator. A human user gives an input – be it a question, statement, or anything else you might think of – and the technology spits an output back at you. In another term, it’s a chatbot – a piece of software that a user can input a message into, and it responds with “its own” generated text.

The idea of talking to a computer and getting a response is not a new one. Since essentially the dawn of the technological age, and even before that in theory and in science fiction, people have dreamed of (and feared) the day when someone could hold a conversation with a computer. As early as the mid-20th century, mathematician and logician Alan Turing proposed the Turing test, outlining his idea for judging whether a computer had the ability to “think” – that is, whether it could interact in a similar enough way to a sentient being that it could not be readily distinguished from one.

With the past introduction of chatbots like Cleverbot and the widespread use of virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, the idea of exchanging ideas with a virtual program is well within mainstream thought. Even so, these examples are limited in use, and can only do so much – one of their biggest limitations being the narrowness of both input options for the user and the outputs of the technology.

With ChatGPT, though, things are different. Services of the past that resemble it, such as the aforementioned Cleverbot, rely on machine learning. Data is entered, and the program uses this data to formulate a response based on specific algorithms, laws of probability and other techniques. The more data available, the better crafted the response can be. Over time, as more and more users interact with the software, it has more and more past interactions to refer to when given a new prompt – and thus becomes better at responding. Taking things to an entirely new level, ChatGPT is grounded on principles which are similar – but not quite the same – and with a degree of processing power behind it that is better now than it was just years ago, and will continue to grow as time continues to pass.

To better understand ChatGPT, there are just a few more technicalities to dive into. Deep Learning is a branch of machine learning that involves the fine-tuning of responses. There are plenty of readings for those interested in all of the specifics of the technology, such as IBM’s blog and other sources, but for the sake of simplicity, the type of technology underneath ChatGPT’s seemingly revolutionary abilities is a much more intricate, developed version of the already discussed machine learning, and it has a decreased reliance on human interaction to succeed. Large Language Models are, in essence, the computed analysis of enormous amounts of data to form correlations and connections, and most importantly, predictions about new data.

ChatGPT is the culmination of the complex and always-changing technology that has just been described. A user can input essentially any prompt, in a perfectly humanlike way, and they will almost always get a coherent response. From “Write a character analysis essay for Edward Fairfax Rochester in Jane Eyre” to “Where is the issue in this code I’m writing?” or “Why did the Soviet Union collapse?,” ChatGPT can craft a response to basically anything someone might think of throwing at it.

And as you might have guessed, this leads us to ChatGPT’s implications in the realm of education.

ChatGPT and the Classroom

As alluded to, the idea that anyone – yes, ‘anyone’ would include a high school student – can give ChatGPT a prompt and get a coherent, humanlike answer in return, has raised red flags throughout the educational world, particularly in the English classroom. Is it now the world we live in where in order to cheat, a student can just ask an A.I. to write their essay?

Thankfully, it’s not that simple.

Or is it?

The Lancer Ledger interviewed English teachers at Lakeland Regional High School to hear firsthand about the reactions to ChatGPT in the academic world. Even before their interviews, the Ledger was made aware of an ongoing discussion between LRHS English teachers that began with a scarily-titled article from The Atlantic, “The End of High-School English.” Among many points made by the article’s author, Daniel Herman, were these key questions: Will writing assignments in English classrooms become obsolete? Will this technology be as revolutionary as inventions like “the printing press, the steam drill, and the light bulb?” And most importantly, will ChatGPT bring about the end of writing as a skill that is learned, mastered, and necessary for success in life? These questions were at the forefront of our minds as we sought the opinions of some of LRHS’ finest.

To start, the Ledger established the initial reactions of these English teachers once ChatGPT made its way into mainstream consciousness. Ms. Jamie Cawley, who was one of the first to bring the matter to the attention of the LRHS faculty, began, “I read an article about it that blew my mind and passed it along to members of the English department. Then after actually playing around with the website myself, I was even more shocked at what this new technology is capable of.” As echoed by Ms. Cawley and many academically-involved figures in and out of Lakeland, ChatGPT is a technology which has appeared rapidly and with capabilities that many never realized would be so readily available.

The initial sense of curious dread that came with ChatGPT’s emergence was further elaborated on by Ms. Melissa Roush, who explained, “I was both intrigued and dismayed by the news. Intrigued that technology has come so far and is capable of such (what I thought) complex thought, but dismayed that it makes it easier for students to cheat and just generally do less thinking for themselves. It is something I can easily see students using to avoid thinking about literature (or anything) if they think they can get an ‘original’ answer or essay from an A.I.”

The Ledger probed further regarding the testing of ChatGPT by some teachers. As reported by Ms. Cawley, “I put in many of my own writing prompts that I give students because I wanted to see how accurate and sophisticated the result would be. What it spit out was most often impressive; however, there were at times inaccuracies and misinformation.”

Ms. Cawley raises a very important point about ChatGPT as a whole: right now, there is no concrete assurance that its outputs are grounded in reality. As stated on the service’s website, “ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers. Fixing this issue is challenging, as: (1) during RL training, there’s currently no source of truth; (2) training the model to be more cautious causes it to decline questions that it can answer correctly; and (3) supervised training misleads the model because the ideal answer depends on what the model knows, rather than what the human demonstrator knows.”

In short, a flaw of the software as a whole is that its methods of finding correlations and making predictions from huge swaths of data do not always yield true information, one of the biggest challenges faced by the technology. Other issues officially acknowledged include excessive verboseness, the making of assumptions about inputs rather than asking for clarification, and the giving of responses to inappropriate or even harmful requests.

These flaws – particularly the flaws in accuracy and composition – hinder the reliability of ChatGPT as a useful tool. Ms. Ann Pagano told the Ledger that ChatGPT “struggled to write a coherent essay.” Highlighting the questionable, and at times completely unreliable quality of response, Ms. Roush noted from her own testing, “Sometimes it was really, really wrong. Like, ‘Poe loves science’ wrong. But, other prompts led it to produce relatively thoughtful, albeit generic, arguments. Although what I saw of it wasn’t ‘good enough’ to use in place of a student generated essay–primarily it lacks use of the text–it could definitely be used by a student to provide direction and basic essay outline that a student could doctor and add to and make their own.”

The idea of ChatGPT as an assistive tool, rather than a machine for creating an outright finished product, is often pondered. While (at least right now) it can’t be trusted to write a solid essay, it can perhaps craft a good enough foundation for a student to edit, add to and submit.

Whether students are generating essays outright or using ChatGPT to create a paper and then modifying it, concerns of unoriginality have, of course, been at the forefront of academic discussion. Ms. Pagano voiced, “Plagiarism is an obvious concern. I already told one sophomore class that if they use an A.I. to write their essays, I will use an A.I. to write their letters of recommendation. The class understood my point.” Ms. Cawley furthered this sentiment, commenting, “Academic integrity is very important to me and I stress this to all my students each year. Aside from ChatGPT, other technology like document sharing and even the internet in general has made plagiarism easy to commit and difficult to detect. It is, no doubt, a rampant problem. We do have useful tools like TurnItIn.com, but the truth of the matter is, we’ll never catch every instance of plagiarism that comes across our desk. All we can do is remind our students why we are here in the first place: to learn and better ourselves. To expand our minds. To be creative, unique thinkers and problem solvers.”

Supporting the concerns about both academic integrity and overall originality by Ms. Cawley and Ms. Pagano, Ms. Roush offered an honest take about where we might be headed. “In class essays only?” she rhetorized. LRHS teachers, especially Ms. Roush, are notably beloved for assigning some essay and other long-form writing assignments as homework rather than as in-class tasks. The new proposition of losing this privilege concerned LRHS students like junior Ryan Susen, who noted, “Certain assignments [are best completed and most academically valuable when] done [at home. I think some at-home tasks are necessary in order for topics to be learned best. At-home essays should still be a thing, because] some people work better from home, but [we must establish a way] that [academic dishonesty] can be avoided.”

Ms. Roush questioned if there might now be “even less thinking by students? More generic essays which I can’t identify as student or A.I. generated. Less student participation as kids assume they’ll just get the A.I. to answer whatever they need. More frustration on the part of those students who are assiduous and interested but sit among students who would rather let a computer think for them than actually entertain or trust their own thoughts.”

To discourage the use of ChatGPT, English teachers at LRHS and around the country are already utilizing services that detect computer-generated text. Ms. Pagano noted, “[I am] already using technology (Draftback, an add on) to detect AI-written text… I told my classes I am doing this.” Ms. Roush, just as concisely, told us, “I already use TurnItIn and Google Plagiarism Check. Otherwise, I will just use locked Google Forms.” (Google Forms being a service for submitting all types of responses to a form creator, which has an optional locked mode that prevents a user from accessing anything else on their computer while the form is open.)

With a final thought on the issue of plagiarism and unoriginality, Ms. Cawley put forth her ideas. “Advice to students: Stop…frequently… before each assignment even, and ask yourself: What kind of person do I want to be? When you steal the work of others, you reap temporary and shallow rewards (if you can get away with it). When you roll up your sleeves and do the work yourself, the spoils are a hundredfold and last a lifetime.”

Ms. Pagano, though voicing concerns about plagiarism and the technology as a whole, shared with the Ledger a more forward attitude toward ChatGPT’s role in the classroom. “I like to ‘Bob Ross’ my essays,” she began, “which means I model how to write. I might try using an A.I. text as a model. The class could grade it using the rubric I always use.” In a perspective where she offered her take on the reality of the situation, Ms. Pagano, who besides her role as a teacher of English also serves as Club Advisor for the LRHS clubs Co-ed Coding and Girls Who Code, continued, “A.I. writing is here to stay and people will use it. For example, realtors already use it to write descriptions of homes. I want to use the technology to boost student engagement. I also want to teach students to use the technology responsibly and ethically.”

Echoing curiosity over positive applications of the technology, Ms. Roush told the Ledger, “Future classes for me may involve many assignments that say: this is what the A.I. did… can you do better?” Many students shared this future-oriented perspective, with senior Nathan Caldwell explaining, “While I will not personally use ChatGPT for class, I believe it will prove to be a useful tool for students and teachers to create worksheets for studying and review.”

The Long-Term

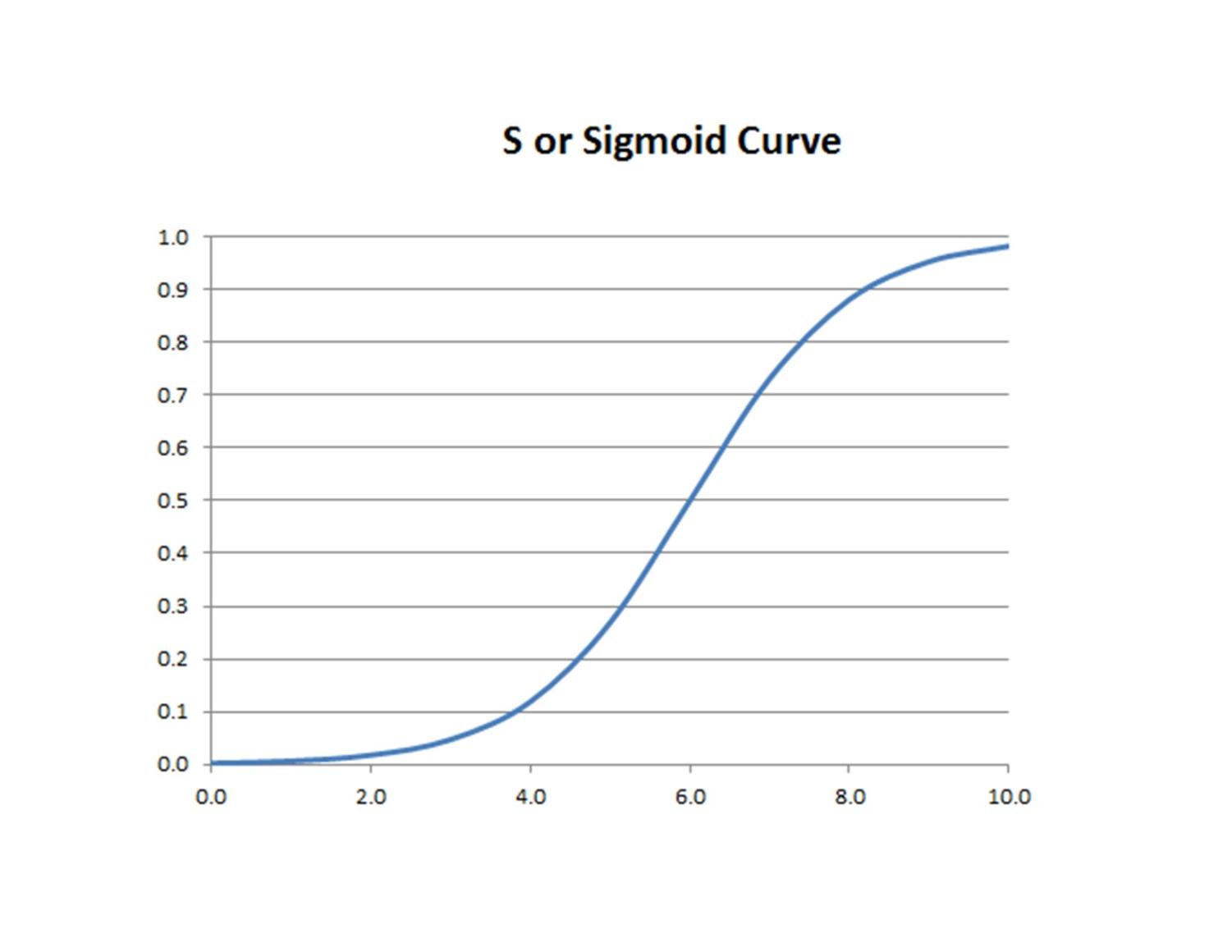

Technological innovation is often said to follow a Sigmoid curve. Sudden, revolutionary breakthrough starts, but it eventually flattens out and change happens very slowly afterwards – for example, the initial introduction of the smartphone compared to the differences in phones over the past couple of years. The catch is that when breakthroughs are still occurring – like the present situation with A.I. – it’s not possible to know when they will slow down.

Two years ago, ChatGPT was a private service that crudely assembled existing ideas into a response. YouTuber Tom Scott uploaded a February 2021 video, “I asked an AI for video ideas, and they were actually good,” in which he broke down where the technology was at the time, and its shortcomings as well as its successes. That was just two years ago – already a year into the pandemic, for those that have lost track of time – and now, Scott’s February 2023 video “I tried using AI. It scared me” juxtaposes his earlier video with the present realization of many of the things which, just twenty-four months prior, were mere theoreticals.

One constant that continues to this point is ChatGPT’s inability to stick to hard facts, i.e., the truth. In the aforementioned video, Scott noted, “I gave ChatGPT a more difficult problem…and it just confidently, completely failed in multiple obvious ways.” But with ChatGPT going in just two years from basic, limited-use phrases to essays, code fixes and philosophical conversations, we truly cannot say where on the Sigmoid curve we currently lie.

Beyond the questions of cheating for a better grade, some have turned to a discussion of the long-term implications of A.I. writing. Will writing as a skill become less valuable because of it? Are we headed to a world where A.I. writing coexists with authentic human work, or even overshadows it? Or will A.I. writing be a fad, used by some low-effort students in an attempt to dishonestly boost their grade but otherwise, exist as just a novelty?

Ms. Roush responded with a twofold consideration. “I think that A.I. has great implications for advertising and all sorts of PR work,” she began. “But I do not think it holds a place in academia. I feel like it cheapens the act of thinking and writing (and making art!). Overall, I see it leading to a sad, scary world in which no one thinks beyond what immediately concerns them.”

Though it’s impossible to predict the future, it may soon be the case that the AI is also able to completely filter its own response for correctness. At that point, essays, research papers, and other works literally write themselves. If this were to be the world we are heading toward, how can we encourage students (and the general populace) to continue engaging in writing as a skill and for pleasure?

In the honest words of Ms. Roush, “This question makes me want to crawl in a hole and not come out. I have no answer except to say that, for me, writing is the forum in which my brain thinks best. I know this is not the case for everyone, but I believe it still is for many. Getting students to write (and write well) is akin to getting them to read and sustain thought. They already don’t want to.”

It’s certainly a scary thought that there’s at least a chance, no matter how small it may be, of heading to a place where writing as a skill and as a talent becomes immensely devalued. “Sometimes going back to basics is the answer. Paper and pen. A unique and thought-provoking prompt,” concluded Ms. Pagano.

ChatGPT, despite the many feats it may be able to accomplish and its overall versatility, raises so many questions about the implications for rational and creative thought in humans, not only in the context of English class but in an overarching, societal sense as well.

Ms. Roush concluded with what, depending on what the future brings, may end up being an oft-echoed sentiment: “It may be time to take out the grid, return to nature and live like Thoreau.”

Stephan Schwab is a senior at LRHS and this is his third year writing for The Lancer Ledger. He is the Editor-in-Chief of The Ledger and President of the...

Chris • Mar 31, 2023 at 9:24 am

Excellent article. Great job Stephan.